Battling biofilms with ColonyCam

When the drugs don’t work…

Abi Sparks1 and Professor Campbell Gourlay2

1 Singer Instruments, 2 University of Kent

Biofilms, multidrug resistance and Candida albicans

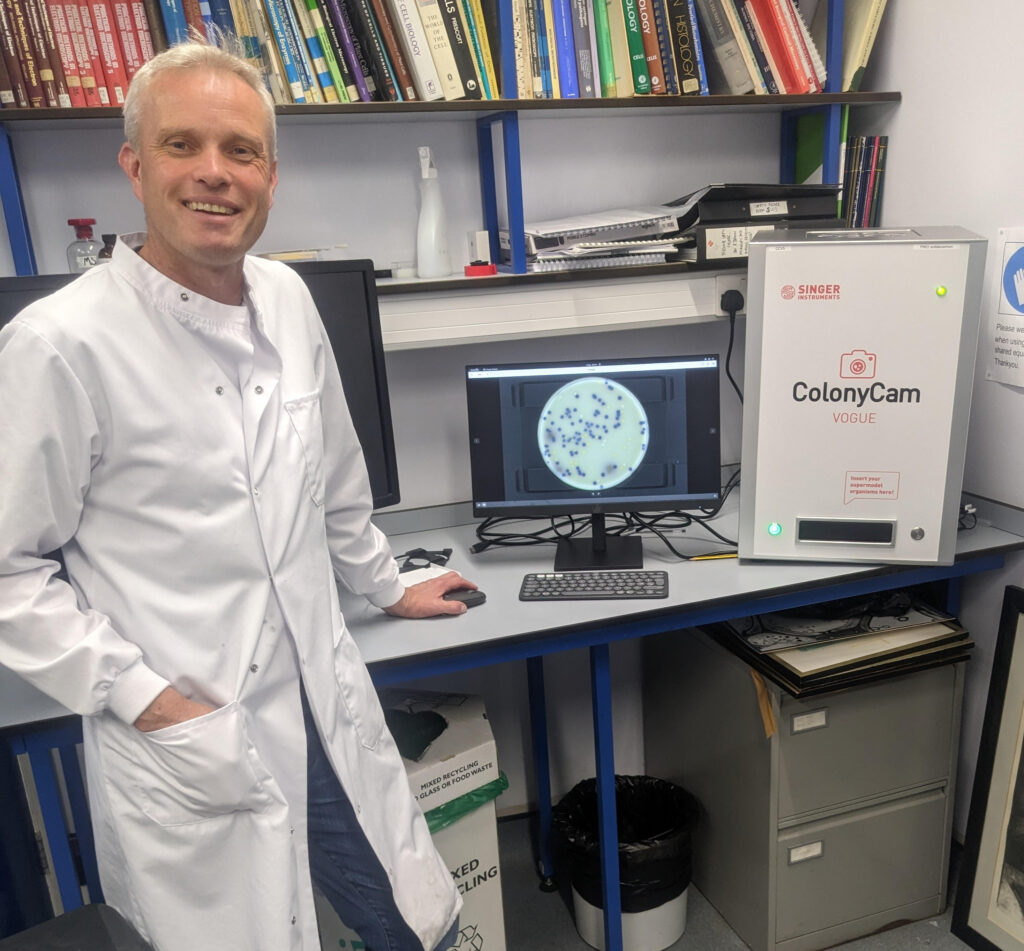

As a budding researcher, Professor Campbell Gourlay focussed on understanding yeast biology, specifically Candida albicans, and is one of the original founders of the Kent Fungal Group. Now, his multidisciplinary team are using the ColonyCam VOGUE to tackle one of the biggest challenges in caring for intubated patients – multidrug resistant (MDR) biofilms.

What are biofilms? Put simply, biofilms are slimy, multicultural communities of bacteria and fungi. Think of a layer of plaque that builds up on your teeth. They can be full of all sorts of cr*p, and are pretty much inherently bad. Bad breath? BIOFILM. Recurrent UTI? BIOFILM. Awful personality? BIOFILM. You get the idea.

Being in a giant blob of slime does have its benefits, though. Biofilms provide protection for those inside against anything external, such as an antimicrobial. Biofilms are harder to completely clear, meaning infections with biofilms are intrinsically more resistant to antimicrobials.

Biofilms form on the breathing tubes of patients, providing pathogens direct access into the lungs, where ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) can develop. The real kicker? Once you have VAP, you have a mortality rate of 10% (Papazian et al., 2020).

Campbell’s work is key, with MDR infections projected to have caused ten million deaths by 2050 (O’Neill, 2016). By unpicking interactions between fungal species and their co-colonising bacteria, they hope to better understand how we can successfully treat patients – or prevent their infections altogether.

Is modelling the answer?

No… not that kind of modelling!

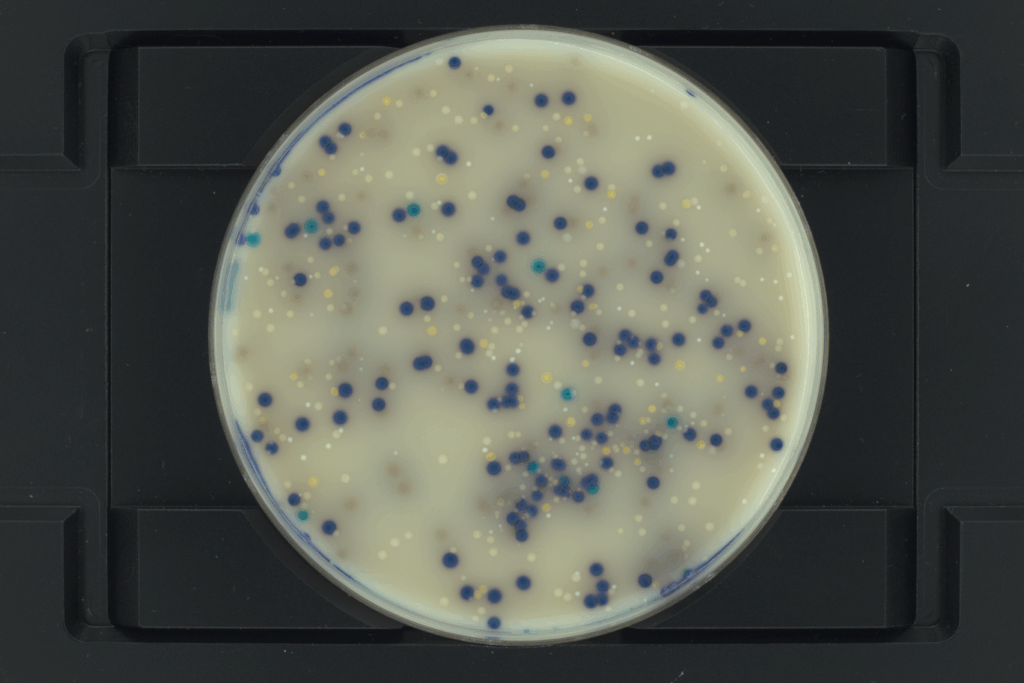

Campbell and his team are using ColonyCam VOGUE to take hi-res images of biofilm-forming colonies. Together with a group in Australia, they are building a mathematical model that can actually predict whether a biofilm is likely to form on an indwelling device. ColonyCam VOGUE has accelerated their research with cool, crisp images that are easy to reproduce. Consequently, Campbell’s lab have been using ColonyCam VOGUE to verify and improve their mathematical model.

“…people were just rocking up, sticking plates in and taking amazing pictures, it just does a better job than any of the microscopes we’ve got. There’s just no faffing around. You get a nice image straight away with one click”

Professor Campbell Gourlay | Professor of Cell Biology

Director of Research and Director of Innovation,

University of Kent School of Natural Sciences

Life before ColonyCam

Before ColonyCam, Campbell’s lab relied on microscopy to capture their colonies. But heavily shadowed images meant hours of careful imaging, cropping and sometimes, even crying. Campbell recalls:

“You would have to take the image one at a time and then kind of crop it … it was actually really difficult. And you get a lot of artifacts because of lighting”.

The ColonyCam’s advanced lighting technology allows a completely flat image to be generated, free of all the usual artefacts. No more tears for Campbell’s lab, only clear images.

Campbell’s lab also tested the newest addition to our ColonyCam range: ColonyCam SILHOUETTE. Offering even better resolution and a backlit image, Campbell has used the SILHOUETTE to generate a publication-ready, crisp image of protein aggregates.

“It just generates nice, publication-ready images”

What’s next for Campbell and his cams?

The ColonyCams sit in that untapped space between micro- and macro-scopy, allowing super hi-res images of colonies, proteins, and whatever else takes your fancy. Campbell has lots of ideas for the future, and plans to do timelapses of leaf-disc assays and C. elegans motility using ColonyCam VOGUE with many more ideas in the pipework.

Are you heading to GAMRIC 2025?

Try our advanced imaging technology and witness ColonyCam’s uncompromising quality for yourself. We’ll see you there!

Abi Sparks | Science communicator

Abi Sparks is a microbiologist who swapped her lab coat for a keyboard as a Science Communications Specialist. She has a PhD in Molecular Microbiology and importantly, a golden retriever called Spud!